Why Oversimplification is Killing African Startups

Lessons on sustainable go-to-market for African startups by Hope Moussi.

“It’s always a big mistake going after a giant market on day one. That’s typically evidence that you haven’t defined the categories correctly, and there’s going to be too much competition. Almost all successful companies in Silicon Valley had some model of starting with small markets and expanding.”

— Peter Thiel

Thiel’s principle, while Silicon Valley-born, holds profound relevance for African startups today. The continent’s entrepreneurial ecosystem is at a crossroads: venture capital flows have slowed, yet opportunities abound for founders willing to embrace nuance over narrative. The tension lies in balancing investor demands for billion-dollar Total Addressable Markets (TAM) with the reality that Africa’s most transformative ventures often emerge from niches dismissed as “too small.”

The TAM Mirage: When Big Numbers Mask Complexity

The allure of large markets is undeniable. Investors gravitate toward startups claiming to serve “Africa’s 650 million unbanked” or “smallholder farmers generating $230 billion in annual output.” Yet these labels obscure critical heterogeneity. Founders often chase large TAMs to align with investor incentives, which can skew early focus. This demand for massive market narratives can pressure startups into premature scaling, chasing an imagined market rather than one grounded in real, high-need customer segments. “.

As investors and operators in Africa’s tech ecosystem, we’ve seen promising startups raise millions, only to collapse within a few years. While many factors contribute to startup failure—poor execution, macroeconomic shocks, regulatory hurdles—one silent killer is oversimplified customer segmentation. Consider three sectors where oversimplification has proven costly:

In 2023 alone, at least 15 African tech startups shut down after raising a combined $200M+. While multiple factors contributed, segmentation misalignment played a role in some of these failures.

- Zumi (Kenya) – Mis-Segmenting B2B Apparel Customers

Zumi launched in 2016 as a women-focused digital media platform but pivoted to e-commerce in 2020. Initially, it targeted direct consumers for online fashion sales, only to realize that its assumption about e-commerce adoption in Kenya was flawed. Co-founder William McCarren later admitted, “People just weren’t converting… Most of these guys are not really buying from websites.” This misalignment led to low sales and unsustainable unit economics.

Realizing this, Zumi shifted to a B2B model, catering to informal apparel retailers in Kenya’s open-air markets. This segment had a stronger pain point—fragmented supply chains—and Zumi’s wholesale aggregation model provided a valuable service. By late 2022, it had facilitated over $20 million in sales from 5,000 retailers. However, while transaction volume grew, thin margins and high last-mile logistics costs made profitability elusive. The startup struggled to scale efficiently and, after failing to raise additional funding, shut down in March 2023. Analysts noted that Zumi eventually found the right segment but ran out of time to refine its monetization strategy.

- Gro Intelligence (Kenya) – Targeting Everyone, But Serving No One Fully

Gro Intelligence sought to become the world’s largest agricultural data platform, serving everyone from smallholder farmers to large agribusinesses and governments. However, this broad segmentation led to a fundamental mismatch between product and market. While Gro pitched AI-driven insights to various stakeholders, its actual revenue depended largely on a few enterprise clients—most notably, Unilever.

The company attempted to sell to government bodies and food security organizations but struggled to secure consistent, repeatable revenue streams. Much of its work became bespoke consulting rather than scalable SaaS. One insider noted, “They were chasing deals that resembled consultancy work rather than something that would generate recurring revenue.” Without a core paying customer base, Gro burned through its $125 million in funding and faced severe cash flow issues. By 2023, it laid off 60% of staff, and in 2024, it shut down entirely. The failure highlights how trying to serve too many segments can dilute focus, making it difficult to sustain a business.

- Edukoya (Nigeria) – Misreading the Education Customer

Edukoya launched in 2021 with a direct-to-student model, offering free digital learning tools and on-demand tutoring. The platform saw rapid user adoption—80,000 students signed up, answering over 15 million practice questions—but monetization lagged. The key issue? Students weren’t the paying customers—parents were.

Unlike competitors that positioned their services toward parents, Edukoya assumed students would drive demand. However, converting free users into paying customers proved difficult. A Techloy analysis noted that Edukoya’s model “failed to gain traction” compared to alternatives like uLesson, which priced its offerings in line with parental spending habits.

Further complicating matters, Edukoya’s business model was misaligned with the affordability of its target market. The startup paid tutors significantly higher wages than traditional teachers, making its cost base unsustainable. By early 2025, Edukoya concluded that chasing scale in a challenging market wasn’t viable and returned remaining funds to investors.

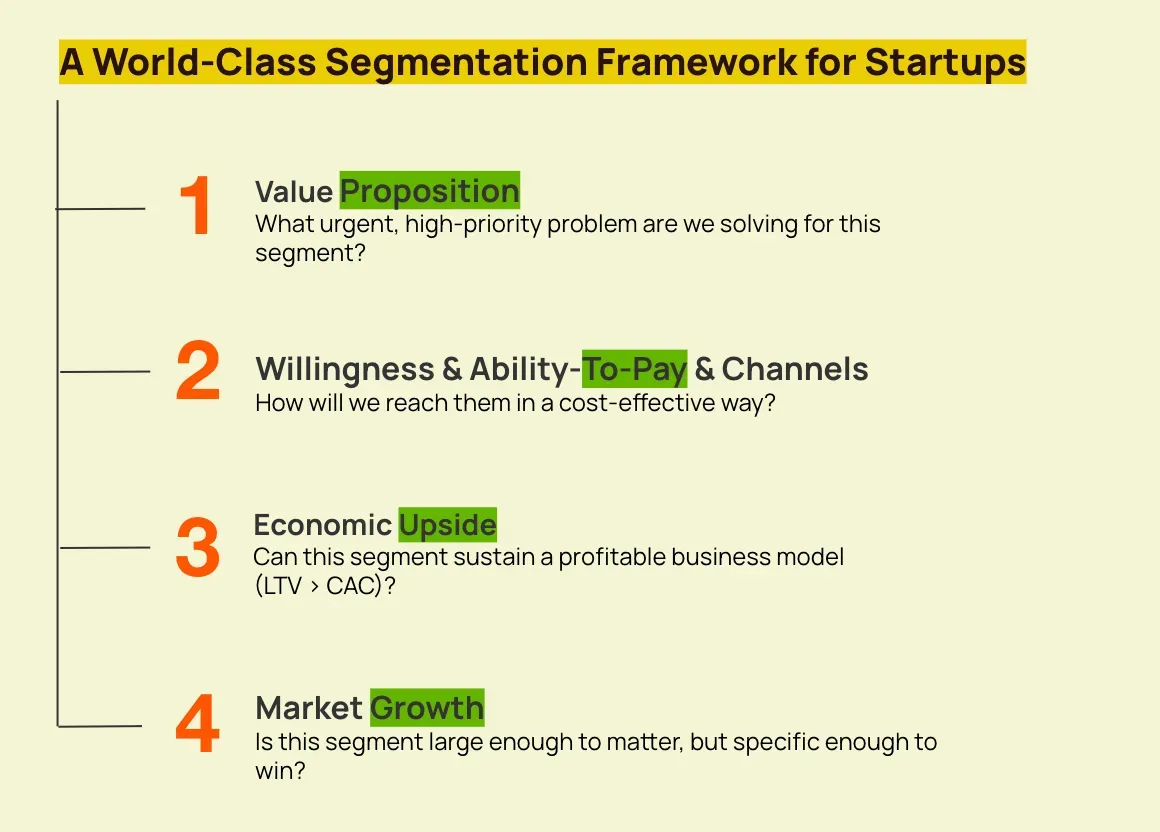

These examples highlight the danger of assuming that a big potential market translates to real demand. Founders must segment customers based on actual behavior, willingness to pay, and distribution challenges—not just demographics or broad industry trends.

By applying this framework, startups prioritize the right customers from day one, improving their chances of survival and growth. Let’s take a look at how Moove executed this well.

Case Study: Moove – A Masterclass in Segmentation

Moove, an African mobility fintech, didn’t start by saying, “We finance cars in Africa.” Instead, it focused on a specific underserved but economically viable segment: ride-hailing drivers who wanted to own cars but lacked financing. Here’s how Moove applied world-class segmentation:

1. Is There a Market? (Market Validation)

Most Africans don’t own cars—not because they don’t want to, but because financing is inaccessible. In Nigeria, only 60 vehicles per 1,000 people exist, compared to 800 per 1,000 in the U.S. Yet, ride-hailing platforms like Uber and Bolt were growing rapidly.

By 2020, Nigeria had 9,000 active Uber drivers, but demand for ride-hailing services still exceeded driver supply. Moove identified a niche, latent market: drivers who could earn steady income but couldn’t buy a car.

2. Is It Underserved, and Do We Have a Strong Value Proposition?

Most traditional banks refused to lend to gig workers, viewing them as too risky. Moove’s value proposition was clear: “Own your car, pay as you earn.”

- Speed: Drivers got vehicles fast—no years of saving required.

- Convenience: Payments were deducted from earnings, ensuring affordability.

- Inclusivity: No credit history required—loan decisions were based on ride earnings.

- Ownership: After repayment, the driver owned the car outright.

By focusing on drivers, Moove turned a previously unbanked segment into a financially viable one, unlocking a path to ownership where none existed before.

3. How Moove Aligns with Disruptor Growth Theories

Moove follows classic disruption and market expansion principles:

- Initial niche dominance: Focusing on Uber/Bolt drivers ensured a captive, high-intent customer base.

- Predictable growth timeline: Like many disruptive models, Moove took 3–5 years to establish credibility, refine risk models, and achieve scale.

- Expansion into adjacent markets: From cars to bikes (UberBoda), logistics, and even U.S. fleet management via its Waymo partnership, Moove has shown horizontal expansion while staying within its mobility financing thesis.

By 2021, Moove had 19,000+ drivers, 850,000 trips completed, and 60% MoM growth, proving its model was both scalable and profitable.

The Takeaway: How Founders Can Apply This

Moove’s success wasn’t luck—it was the result of disciplined customer segmentation. If you’re building a startup, here are the key questions to stress-test your market:

- Is There a Market? Validate demand with real data, not assumptions.

- Is It Underserved? If there’s no clear pain point, customers won’t switch.

- Is It Economic? Run unit economics early—does this segment make financial sense?

Many African startups fail not because the opportunity isn’t big, but because they target the wrong customers too broadly. The next wave of successful founders will win by starting small, segmenting well, and scaling methodically—just like Moove.

If you're building, investing, or advising in this space, let’s connect. The future of Africa’s startup ecosystem will be shaped by those who understand their customers best. 🚀